Ian Humphreys

Local writer and storyteller, George Murphy interviews local characters and personalities. More HebWeb interviews

Introduction

George Murphy: Happy New Year and welcome to the latest interview with a talented local. I've been a big fan of Ian Humphreys' writing, so I was delighted that Ian found time in his busy schedule to talk about his life, his work and his response to living in Hebden Bridge.

George Murphy: Happy New Year and welcome to the latest interview with a talented local. I've been a big fan of Ian Humphreys' writing, so I was delighted that Ian found time in his busy schedule to talk about his life, his work and his response to living in Hebden Bridge.

Ian is currently the Writer in Residence at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. His writing bibliography is included below.

We met for a chat at a local pub before the holiday period. I felt I wanted to focus on Ian rather than, say, giant wind turbines! Here's his responses to the questions I sent him.

Ian Humphreys Q&A

Ian, you made a late start as a poet?

I enjoyed writing poetry at primary school, and occasionally made small booklets of my poems to post to my great aunt in Hong Kong who was an English teacher. My interest waned dramatically after that until, about thirty-five years later, I moved to Hebden Bridge and joined a WEA poetry course run by poet and tutor Sally Baker.

When did you realise you had found your vocation?

When did you realise you had found your vocation?

The first WEA writing course I signed up for was about writing short stories. I switched to poetry just for a change of scene. I hadn't written – maybe even read – a poem in almost three decades. After completing that first poetry writing exercise though, something clicked. I was hooked.

You have written about your complicated DNA; can you tell us about your family?

My late father was Anglo-Irish. He was brought up on the Kent coast and, when I was a child, we'd visit relatives there most summer holidays. My mum was born and raised in Hong Kong. But her background was multi-heritage – an interesting and mysterious mix of mainly Asian and African. I've written quite a bit on her complex ancestry, and on my own mixed heritage; about the ups and downs, pros and cons of being 'other' (and 'othered') in terms of race as well as sexuality.

How was school and HE?

I loved school until age 11. After that it was OK, a bit uninspiring to be honest. I also withdrew into my shell around the age of twelve. The usual story: gay kid discovers they're different but longs to be like everyone else; a tale of shame, guilt, and worrying if you're going to grow up to be the next Larry Grayson.

My journey to poetry involved doing an MA in Creative Writing at the Manchester Writing School (MMU) and that was a joy. My co-students were brilliant and supportive, and we were blessed with incredible tutors like Jean Sprackland, Carol Ann Duffy and Michael Symmons Roberts.

In Zebra, you reference Edmund White's 'A boy's own story'… who were your literary heroes at that time?

I came across Edmund White in my late teens after leaving home, and it was a revelation to read about queer life in the 50s, 60s and 70s. Around the same time I discovered other writers exploring LGBTQ+ themes; novelists like James Baldwin, Christopher Isherwood, Truman Capote, Andrew Holleran, and a bit later, Jeanette Winterson and Alan Hollinghurst.

You came of age in the 80s. Which clubs, pubs and bars did you frequent?

I first stepped out at the Manchester Youth Group which in the early 80s was located just off Canal Street. Canal Street was a bit grim back then; no glitz, no spritzers. I loved it. Very rough and ready, just like the drag queens in Stuffed Olives. My favourite club was High Society, which seemed very classy to me (a boy from semi-rural Cheshire) with its swirls of dry ice and light up dance floor. We'd shake our shoulder pads to a Hi-NRG beat while high on Kouros by Yves Saint Laurent. I remember the Hacienda tried to host a regular gay night around 1985 – it bombed. The place felt cavernous, empty, the industrial vibe too ahead of its time. The bouncers were charming though, helping us on and off with our coats as if we were VIPS.

What was the gay scene like during the AIDS crisis?

By the time AIDS reached crisis level in the UK, I'd already left for Hong Kong, dutifully following Norman Tebbit's 'onyerbike' advice to escape unemployment. But I remember the awful newspaper headlines and the fearmongering in those early years. I'll also never forget my first day at the Gay Youth Group; we were sat in a circle and told about this mystery disease from the States, and warned not to sleep with anyone from San Francisco. It was terrifying, of course, as no-one knew at the time exactly how the virus was transmitted. When I look back, there are echoes of the homophobic hysteria that would later surround gay teachers and Section 28, and also similarities to what's happening today with the prejudice directed towards the trans community.

Do you consciously seek to use a variety of poetic forms? And is humour something you enjoy using in your work?

Personally, I admire variety and texture in a book of poetry and that's what I aim to create. I enjoy being surprised by different shapes, forms and styles as I turn the page. And when I write, I like to experiment and play rather than adopt a more uniform approach. That's partly why I'm drawn to humour - the playful side of it; the disruption or gut-punch of placing a funny poem next to a dark or serious one; the tension of exploring sombre, challenging material with a smile or a laugh. I also like to write direct, accessible poems as well as more obscure, shadowy or surreal pieces.

There's quite a bit of snobbery around some poetic styles; accessible and obviously political poems, for example, are frowned upon by certain poets and editors. Subtlety in a poem is often held up as being somehow intellectually superior, an enigma that warrants interrogation by the academic mind. I suspect, however, that many subtle, opaque poems are simply sphinxes with no secret. The flip side to that, of course, is that so-called accessible poems often hold hidden complexities through line breaks, language, shape and allusion.

Ian with Twm (Snow)

Is walking one of your hobbies?

I began hiking when I was living in Hong Kong, after meeting my partner Nigel who was already a keen walker. Being raised in rural Wales, he could read a map, and knew a red-whiskered bulbul from a redstart. Back then – thirty-plus years ago – hiking wasn't a popular pastime in Hong Kong, and you didn't cross paths with many fellow walkers while on a mountain trail or in a country park. Walking's my only form of exercise now – for body and mind. I can step out of my front door and be on the moors in 15 minutes which I still find incredible.

Is a habit of keen observation something you teach to your students?

Observation is important in any genre of literature or any art form. Reminding yourself to look or listen or touch. Finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. Taking notes. Basically, it's good practice to develop your gaze, and make it appear on the page to be unique to you. I have a tendency to observe the world as an outsider looking in; there might be a hint of anxiety, there's often a circling of the subject, viewing it from different angles, and the inevitable failure to get at the truth of the thing.

On social media, you often post photos of your Jack Russell, Twm, 'flying' on the moors. Have you written any dog poems?

There's a dog poem in my first book, Zebra, about someone who starts behaving like a dog after being ditched by their lover. There's also a poem in my latest book, Tormentil, called 'Rubber Pup at the Gay Rights in Chechnya Rally'. And Emily Brontë's bullmastiff cross, Keeper, features in a poem I've written for my Brontë Parsonage Museum residency.

Can you tell us a bit more about your role as Writer in Residence at the Brontë Parsonage Museum?

I was honoured to be appointed in the role for a year, until March 2024. Over the summer, I led walking and writing workshops on Haworth Moor with various social groups. During these walkshops, hundreds of haiku were written, many by people who had never written a haiku or even a poem before. Each of these tiny poems was inspired by the wild, by nature and by the Brontës. Many of the haiku will feature in an installation at the Parsonage from mid-January to mid-February. Visitors in need of a 'pick-me-up' during the long, dark winter can pick up a haiku from our vintage first aid kit and hopefully enjoy a feel-good 'lift', a ray of poetic sunshine – therapeutically, spiritually or cerebrally.

Several poems in my latest collection came out of the early months of the residency, and I've written further work which will be shared in the form of a poetry audio trail in the grounds of the Parsonage and in Parson's Field. I'm also editing an anthology of prose poems, inspired, in some way, by the Brontës and the wild moors, and written by local poets, and writers with a connection to the Parsonage. The book, to be published by Calder Valley Poetry, has the working title 'Untamed' and will be launched in June this year.

Favourite book?

Alma Cogan by Gordon Burn. Ariel by Sylvia Plath. Quite a few by James Baldwin. Anything by Alan Garner.

Favourite TV series?

The Wire. Mad Men. Our Friends in the North. Coronation Street (1976 to 1983).

Favourite piece of music?

'Hounds of Love' by Kate Bush. 'Screamadelica' by Primal Scream. 'Debut' by Bjork. A lot by Prince. A lot by Grace Jones. Anything by Kate Bush actually. Klaus Nomi singing The Cold Song.

Can you tell us about your Sylvia Plath project in 2022?

The Sylvia Plath project was a two-part production: the book and the festival. I first started work on the rather ambitious plan alongside poet and Plath expert Sarah Corbett in late 2019 at the funding stage. Like so many, we were scuppered by the Pandemic. When we started up again, Sarah and I decided to split the project in two to better manage workload. I took creative lead on the book After Sylvia, and Sarah grasped the reins on the Sylvia Plath Literary Festival. It was an expansive, international project that took up a lot of our (mainly unpaid) time, but the reaction to both festival and anthology made it 100% worthwhile. Most rewarding of all, it seemed to help bring the work, legacy and life of Sylvia Plath to a new, more diverse audience.

Why I Write Poetry - what were your criteria for choosing the topics and the poets?

I wanted the book to represent a cross-section of today's poetry scene in the UK. Thankfully, when I began to list the poets whose work I admire, a breadth and scope of distinctive, dissimilar voices began to take shape naturally. This was very satisfying, as was the fact that my choice of poets wasn't London-centric. Authors with many collections under their belts sit alongside newer names, and contributors originate from all corners of the UK and beyond. There are poets represented by big publishers, others championed by small independents. Some contributors write in English as a second language, some use dialect. A few are dismantling the barriers between page and stage. But they all have one thing in common - a desire to write towards their own particular truth. This truth, this personal obsession is what I asked each author to touch on in their essay.

How was lockdown for you?

Not great, especially the first few months. My mum died of Covid right at the beginning of the Pandemic when the whole world was in panic mode. Her death was the catalyst for my new book, Tormentil. The collection looks at loss in various ways, through multiple lenses, rather than focussing solely on the loss of a loved one. Losses in the natural world is a major theme, another is the gradual and worrying loss of hard-won freedoms as global societies veer to the right and populism. One or two poems also explore how we as humans seem to be losing our humanity, losing our way. There's also plenty to smile about, I hope, in the book. Many poems pay homage to nature and her resilience, others explore the uniqueness of our moorlands, peat bogs, flora and fauna. And family, food and human relationships

are held up to the light, scrutinised, and celebrated.

Not great, especially the first few months. My mum died of Covid right at the beginning of the Pandemic when the whole world was in panic mode. Her death was the catalyst for my new book, Tormentil. The collection looks at loss in various ways, through multiple lenses, rather than focussing solely on the loss of a loved one. Losses in the natural world is a major theme, another is the gradual and worrying loss of hard-won freedoms as global societies veer to the right and populism. One or two poems also explore how we as humans seem to be losing our humanity, losing our way. There's also plenty to smile about, I hope, in the book. Many poems pay homage to nature and her resilience, others explore the uniqueness of our moorlands, peat bogs, flora and fauna. And family, food and human relationships

are held up to the light, scrutinised, and celebrated.

Good and bad of living in Hebden?

Lots of stark, beautiful countryside. Lots of mosses, lichen and ferns. Lots of rain. Lots of community spirit. Lots of dogs. Lots of poets. Lots of cafes to sit in and pretend to write poetry.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Author:

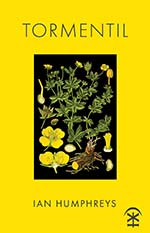

Tormentil (Nine Arches Press, 2023)

Humphreys' poems are astonishingly colourful, metaphorically acute and highly persuasive. – A Yorkshire Times 'Book of the Year'

This is a moving and powerful collection that will be read and re-read for years to come. - Kim Moore

Zebra (Nine Arches Press, 2019)

Humphreys' poems have deep emotional capacity – Poetry London

Zebra has come out to a deluge of praise and it's easy to see why – The High Window

Editor:

After Sylvia (Nine Arches Press, 2022)

'Here, 60 established and emerging poets celebrate Plath's influence.'

– The Guardian (Best Recent Poetry Book Choice)

Why I Write Poetry (Nine Arches Press, 2021)

'This is a startling book, with far more reach, truth, and daring than most books that are attempted on the subject.' – David Morley

More HebWeb interviews from George Murphy

If you would like to send a message about this interview or suggest ideas for further interviews, please email George Murphy