Simon Manfield

Local writer and storyteller, George Murphy interviews local characters and personalities. More HebWeb interviews

Introduction

George Murphy's latest interview reveals the life and career of artist Simon Manfield. A man who crossed the world to find a place that feels like home. Simon shares reflections on his childhood in Australia, his love of drawing and how he was inspired by the works of George Mackay Brown.

George Murphy's latest interview reveals the life and career of artist Simon Manfield. A man who crossed the world to find a place that feels like home. Simon shares reflections on his childhood in Australia, his love of drawing and how he was inspired by the works of George Mackay Brown.

He also details the events leading up to his brilliant and moving depiction of the uncovering of the remains of Spaniards slain by Franco's firing squads during the Spanish Civil War.

Simon, you grew up in Australia. Can you tell us about your early years? How did you like the lifestyle and the climate?

Thank you for inviting me to do this interview, George. It’s an interesting process putting recollections of the past into words; those small details buried away over the years, to be given light and air again.

Yes, my family, that is my mother, father, two elder brothers and I (21 months old), joined the movement of Brits, or ‘Ten Pound Poms’, lured to adopt new lives in Australia. We left the UK on-board the P&O liner, SS Strathnaver arriving in Melbourne, Victoria on 1st October 1961; we then settled in Sydney, New South Wales, specifically Newport in the Northern Beaches, three years later. Newport is a beach suburb by the Pacific Ocean, 32 kms from the city of Sydney. At the time of our arrival, it had an unspoiled, even rural setting. It wasn’t until much later I realised just how idyllic it was. It was then, and still is now, an important surfing beach on the Pittwater peninsula.

Mum, my two brothers and I in Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

en route to Australia, 1961

The lifestyle was near perfect for a child. I had some good friends, explored the bushland around, and the sea was just minutes away. I loved the sound of the cacophony of the dawn chorus as I delivered the Manly Daily, the local newspaper, on my bike before school. Outside of school I felt a freedom to explore that landscape, but I felt most free in my imagination. I was a dreamer, and school just got in the way. We had a lot of American television in Australia, shows such as Daniel Boone, or Kirk Douglas in The Vikings, but also Australian outback adventures with Chips Rafferty offered unrestrained space to allow the imagination to run riot. I read books on Native Americans and anything Viking by Henry Treece.

I tried surfing and Rugby Union, but unlike my peers didn’t fall comfortably into a sporting way of life. I was of course, that red-haired, pale-skinned ‘Pom’ who made drawings and was prone to blistering from the sun; an outsider, a bit of an oddity. A change in acceptance, both of me and for me, came at the age of 16 after leaving school. I was introduced to another way of life that better suited me; but more of that later.

Your family were ‘Ten Pound Poms’. Were both your parents in full time employment?

My dad had for many years wanted to move to Australia. He and a pal had envisaged setting up a poultry farm (Guinea fowl, I think) in Tasmania, years before meeting my mum. The former didn’t happen, but of course the latter did.

We were fortunate migrants as my dad had a job already lined up. He worked as a salesman in the carpet trade in the UK, and continued that work, first in Melbourne then with a transfer, in Sydney. My mum had been a graphic designer in the UK, her claim to fame being the designer and lettering artist of the Harrods logo, but in our early years she had put her brushes aside to raise us three boys. The brushes were eventually taken up again in later years. She returned to graphic design work but also as a visual artist in her own right, producing beautifully sensitive landscapes and flower paintings.

My mum and dad separated, and then divorced in the late 70s; they both remarried and for a time lived happy new lives. My mum married an old friend from the UK, Dan Escott, a well-respected heraldic artist. Dan emigrated to Australia in 1983 to begin a new life with my mum but very sadly died of cancer in 1987. My mum still lives in the Northern Beaches and is wearing her 95 years well.

In about the mid-80s my dad, with his new wife Jan, moved to a rambling weatherboard house in Kendall, a rural town on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. Throughout my childhood, my dad showed a firm interest in what I was doing with my drawing. Later he spoke of his envy of my skill. After retiring, he started making lovely watercolour studies of birds, flowers and landscapes, and he was always keen for my opinion on them. He died in 2014.

Did you always want to be an artist? Were you able to get onto art courses in your teens?

It wasn’t until I was older that I desired the life of an artist. Growing up, I always made drawings and did have a visual talent, but I never considered being an artist as a career choice. What I wanted then was to study to be an archaeologist, an anthropologist, or an architect but, as alluded to earlier, I just didn’t have the academic acumen to allow that to come to pass.

With gentle persuasion and true understanding my parents proposed an alternative educational route. In 1976 I began a 2-year Art Certificate course at Seaforth Technical College, a course introducing me to a foundation of skills and disciplines. Completing that course, I continued my studies for the next 3 years at Alexander Mackie School of Art in the Rocks, Sydney. Both experiences were invaluable, mostly due to the introduction to like-minded people but also teaching me the fundamentals of two disciplines I would carry with me into my present arts practice: drawing and photography. Sadly though, and as is often the case, I left further education without a definitive idea of where to go and what to do with these new skills.

With gentle persuasion and true understanding my parents proposed an alternative educational route. In 1976 I began a 2-year Art Certificate course at Seaforth Technical College, a course introducing me to a foundation of skills and disciplines. Completing that course, I continued my studies for the next 3 years at Alexander Mackie School of Art in the Rocks, Sydney. Both experiences were invaluable, mostly due to the introduction to like-minded people but also teaching me the fundamentals of two disciplines I would carry with me into my present arts practice: drawing and photography. Sadly though, and as is often the case, I left further education without a definitive idea of where to go and what to do with these new skills.

Your family stayed down under. What motivated you to move to the UK? Did you change your opinion about Australia in later years?

I tried leaving Australia a couple of times in the early 80s. Like many Australians before me I was trying to feed an urge to find my own way, to shake off the red dust, to immerse myself in what I thought at the time was the cultural centre, the old world: Europe. I also found Australia too far away, isolated and separated from the rest of the world. Australia has every conceivable landscape, but I was overwhelmed by it, and I just didn’t feel a connection or belonging.

On both those earlier trips I ran out of money, each within the year, but they confirmed an ongoing love for Europe and its richness of colour and character. Looking back I could easily have delayed the retreat back to Australia, but I was young and inexperienced in the world. What I lacked in experience, I made up for in tenacity.

On my third and, as it turned out, final trip in 1988, I got off a bus on Princes Street in Edinburgh. I felt as if a warm hand touched my shoulder. For a time, I was home. Wherever I was though, what I was looking for then, and still am to some extent, was somewhere I felt I knew well, that was mine, and somewhere I could walk unchecked.

In 2002, I moved to Hebden Bridge to be with my then partner. It was a big move for me, and for a while I missed Edinburgh, Scotland and the family of friends I’d made there terribly. Time has moved on and I’m happy where I am just now and have made a family of friends here too. There is still a part of me that is looking for that other place though. I am my father’s son; I felt he was looking for something else too, whatever that something else was.

In 2008, 20 years after leaving Australia, I returned to see my family and some old friends. There was a lot to catch up on. Most of my immediate family had visited me in the UK but some hadn’t. Over those 20 years I had learned a great deal about myself; it was an important trip for me. I remember being back in Hebden Bridge, walking to work, and feeling very tall, head held high. Any misgivings I’d once had about Australia had been diluted over the years and I feel at peace with that place now. I happily visit every couple of years.

My Dad and I, Kendall, 2012

You’ve worked in a variety of styles, yet emphasise the importance of drawing in all your work. Is that something you pass on to your students?

Drawing is my primary discipline. I love its immediacy; it can be a quick sketch; it can be a more complex concentration of thought. Drawing is all about thinking, about observing and understanding the world around us and getting it down on whatever surface you are working on, using whatever marks with whatever tools and whatever media you choose. It can be done anywhere, and everybody can do it!

What I do want to pass on to students is that drawing shouldn’t just be considered an adjunct to painting, a preparatory step towards something greater or more important. Drawing as a discipline is itself that something greater and important. Fundamentally, it is the passion I feel for drawing that I want to pass on to students.

You found inspiration in the writing of the Orcadian George Mackay Brown. Can you tell us about him and your response to his work?

Chicken (Orcadians: Seven Impromptus), 2013. Gouache on paper.

I was introduced to the writing of George Mackay Brown by an Orcadian friend while working as a bookseller in Edinburgh in the late 80s. GMB’s writing is so beautifully considered and comes deep from within his soul and spirit, from a true emotional understanding and love for his home, Orkney. His words come as images to me, but at the time of my introduction I didn’t feel a competent enough draughtsman to do those words justice. It wasn’t until the publication of The Collected Poems of George Mackay Brown (2005), and time spent building confidence in my drawing skills and gaining more practical experience that I felt more ready to take something on.

Crofter (Orcadians: Seven Impromptus), 2010. Ink on paper.

The poem that jumped out at me in the vast collection was the poem cycle ‘Orcadians: Seven Impromptus’, from his first collection of poetry, The Storm and Other Poems (1954). It wasn’t until 2008 that I started making the drawings that would eventually be published as Orcadians: Seven Impromptus as a limited hardbound edition in 2016 by James Robertson’s small publishing house Kettillonia. It was a pure labour of love for me; a slow and reflective process, not only in relation to my visual responses to the poem cycle but in the measured development of my drawing practice.

Some questions from readers:

How was lockdown for you?

The first lockdown was a magical time for me, and very productive. The weather was warm and fragrant, and I felt a wonderful release from any pressures; an enforced break from the growl of 21st century life. The following two lockdowns however did not have as sweet a taste.

What are your hobbies?

All I enjoy and love relate to my creative work. When I walk, read, listen to music I think in visual terms and reflect on how to put those thoughts down in two dimensions. They are occasions to give me space to think about how to express myself visually. My life is one big hobby (well, almost), and I’m very lucky.

How do you relax?

As above.

Favourite artists?

Rembrandt, Velásquez, Degas, always Picasso, always Matisse, Arthur Melville, Eduardo Chillida, Antonio Lopéz García, Käthe Kollwitz, Joan Eardley, Euan Uglow, Jon Schueler, John Byrne, James Morrison, and, and, and …others.

Favourite music?

It depends on my mood but the pile of CDs in my studio at the moment are Mingus Moves (Charles Mingus), Mondi Caldi Di Notte (Italian 60s Mondo Movie Sexy Themes), Betty Blue 37°2 Le Matin (Music from the film), Bonhomme (Georges Brassens) and Construção (Chico Buarque). Tomorrow may well be different.

What luxuries would you want on a desert (or partly desert) island?

Something to draw with and on… perhaps a hefty supply of good strong cheddar with innumerable loaves of crusty bread, if that’s allowed?

Favourite film?

Again, it depends on my mood, but I never tire of watching Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird, or Cinema Paradiso. I like a good cry.

Can you tell us about the paid employment you’ve had over the years? When we met you mentioned an organisation called the Open College of the Arts. What is their role?

Since about 1979 I’ve had many jobs as a bookseller, both part-time and full-time, in Australia, Scotland and now at the Book Case in Hebden Bridge. It’s been a job that has sustained me over the past 40 odd years, with I think only four years off to travel, study and to spend time developing my practice.

In between and at the same time, especially after leaving Australia, I have had various commissions for my artwork. The job that really started the ball rolling was as illustrator and cover artist with the Scottish political magazine, Radical Scotland in the late 80s and early 90s. With that came illustration jobs making cover artwork for Greentrax Records and cover designs and internal illustrations for publishing houses such as Kettillonia and B&W Publishing.

Collaborating with artists, curators and designers (Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sullivan, Sarah Tripp, Jason E. Bowman and James Langdon) has also become an important addition to my arts practice. My most recent is a wonderful collaborative relationship with musicians Georgia Mancio and Alan Broadbent, creating artwork for their two albums, Songbook (2017) and Quiet Is The Star (2021). A third album is in preparation just now.

With an exhibition of my artwork at the University of Bradford’s Gallery II in 2006, I was offered a teaching role to give life drawing classes to their students of Gaming and Animation. This led to a regular post which offered more hours, to teach observational drawing at the university. My teaching portfolio was steadily gaining pace!

Alongside my university work I started overseeing life drawing sessions locally at Artsmill and Northlight Art Studios in Hebden Bridge, and alongside that, from 2012 I started tutoring for the Open College of the Arts, a distance learning organisation based in Barnsley.

I was made redundant from Bradford in 2016, and my local teaching had reduced its hours with the ceasing of sessions at Artsmill. I still run regular life drawing classes for Northlight, and continue my role as a drawing tutor with the Open College of the Arts (OCA). The OCA was created as a distance learning provider of higher education arts courses in 1987. Until fairly recently it had been run as an independent but in August 2023 it joined forces with the Open University. Since beginning with the OCA I have been a tutor of illustration and drawing, and have co-authored a couple of courses (A Personal Approach to Drawing, and Drawing Practices) for the organisation.

Noticing your limited edition book on George Mackay Brown, I’ve become besotted by his prose works - it’s said he helped to set a new trend in travel writing - and I’ve started to read his poetry. My homework is The Orkneyinga Sagas! So thank you for that. But I also remember being fascinated and moved by your series of illustrations from Spain. Can you share examples of that work and explain how you got involved?

I am always more than happy to speak about my work from Spain. Making that work, called as a collection Memoria Histórica, was a real turning point for me and for my confidence in the work I made. I am immensely proud of the collection and look back on that time in July 2003 with emotion. It was the first time I felt that the work I made held weight and importance.

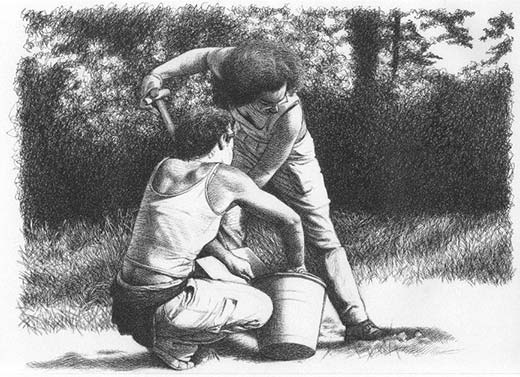

On site, Valdediós (Memoria Histórica), 2004. Ink pen on paper

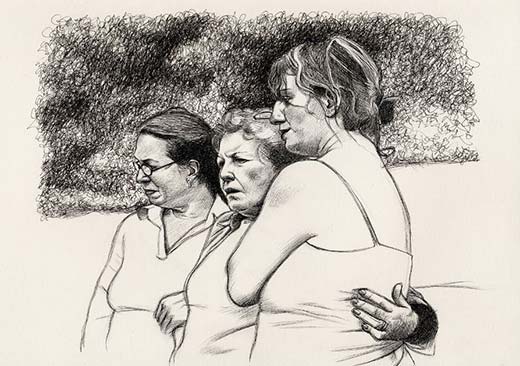

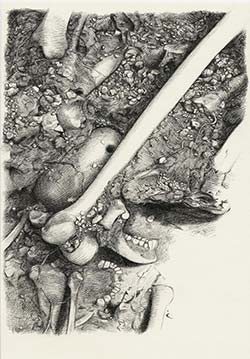

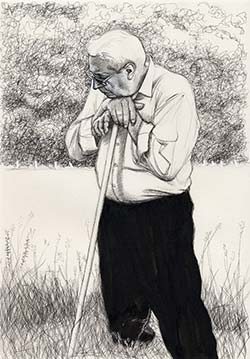

In early March 2003 I read an article in the Guardian by Giles Tremlett entitled, ‘Spain’s civil war comes back to life’. It spoke of the excavation of a grave containing the bodies of three women from Poyales del Hoyo in Ávila. They had been murdered in December 1936 by an execution squad working for General Francisco Franco’s rebel forces. At the end of the article a call for volunteers was made to take part in further excavations. I applied immediately, wanting in some way to be involved. With barely any Spanish at the time I hoped my skills as a visual artist could be beneficial in recording another of the excavations.

I contacted the International Voluntary Services in Leeds, who passed on my application to the association organising other excavations in Spain. The Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (ARMH) accepted my application. The excavation I was to take part in was in the small hamlet of Valdediós, Asturias in the north of Spain.

(Memoria Histórica), 2004

Over a period of about three weeks a group of international volunteers and archaeologists worked with picks and shovels in a sloping meadow searching for a grave containing the bodies of medical personnel murdered by another of Franco’s execution squads in October 1937. By the end of the second week we had still not found the grave; testimonies from visitors to the site led us from one end of the meadow to the other; frustrations and tempers began to flare, to the point that it appeared as if the excavation would not go ahead. Six volunteers and two team leaders abruptly left the excavation.

(Memoria Histórica), 2004

At the beginning of the third week, the head of the ARMH, Emilio Silva, arrived with Forensic Archaeologist Francisco (Paco) Etxeberria and Anthropologist Lourdes Herrasti to rescue the failing project. With them came a mechanical digger and an experienced driver. These four additions made all the difference to the success of the continuing process.

We located the grave at the bottom of the meadow on 24th July, finding the remains of 18 of a possible 29. The recovered bodies were taken away for DNA testing in the August. Perhaps the most poignant moment was when Antonio Piedrafita, son of one of the murdered, was called by one of the archaeologists. The shattered skull of his father, identified by a row of gold teeth, lay atop another body at the corner of the L-shaped grave.

Memoria Histórica is a collection of 60 drawings in various media, all A4 in size, documenting that unforgettable moment of recuperation for those families whose relatives lay in that terrible grave. Some of those relatives and some of those volunteers remain the closest of friends.

I believe you’ll be enjoying an Artist’s Residency on a yacht in the very near future. Please tell us about that.

Yes, I am thrilled to have been accepted as Artist in Residence to help celebrate the centenary of the building of Provident of Brixham, a beautiful ketch-rigged former trawler at the end of May. I will be on-board for the four days of a regatta held in her honour, making preparatory studies to produce a ‘portrait’ of her under sail over the month of June, to then make into prints. I’m looking forward to seeing the direction this work goes. I’ll have a better idea once I disembark after the regatta. I’ll let you know more about it on completion of the work!

Simon, is there a question you wished I’d asked, and how would you have answered it?

Boreray and the stacs (Monument and memory), 2021. Gouache on paper.

Perhaps a question about the only missing project of mine spoken about here, one entitled Monument and memory. Monument and memory is an ongoing project that, like my other projects, follows themes of historical memory and narrative, engaging with the passage of time and its effects on humanity and the environments it occupies and inhabits. The drawings, a couple of which are represented here depict the relationship between the St Kilda archipelago’s monumental landscape, the sea that surrounds it, its people and how over history each has left its mark on the other.

More information about this and any of my other projects can be found on my website: www.simonmanfieldartist.co.uk

More HebWeb interviews from George Murphy

If you would like to send a message about this interview or suggest ideas for further interviews, please email George Murphy